In August 2018, the town of Arua became the stage for one of the most dramatic and controversial political episodes in Uganda’s recent history. What began as a by-election campaign in Arua Municipality quickly descended into chaos, violence and arrests. This left behind a trail of unresolved questions that continue to haunt the country’s political and justice systems years later.

At the centre of the storm was Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, popularly known as Bobi Wine, then the Member of Parliament for Kyadondo East and an increasingly influential critic of President Yoweri Museveni (M7). During the campaign period, President Museveni visited Arua to support the ruling party’s candidate. Shortly after his departure, reports emerged that the presidential convoy had been stoned, damaging at least one vehicle. Within hours, security forces launched a sweeping crackdown on opposition supporters and leaders.

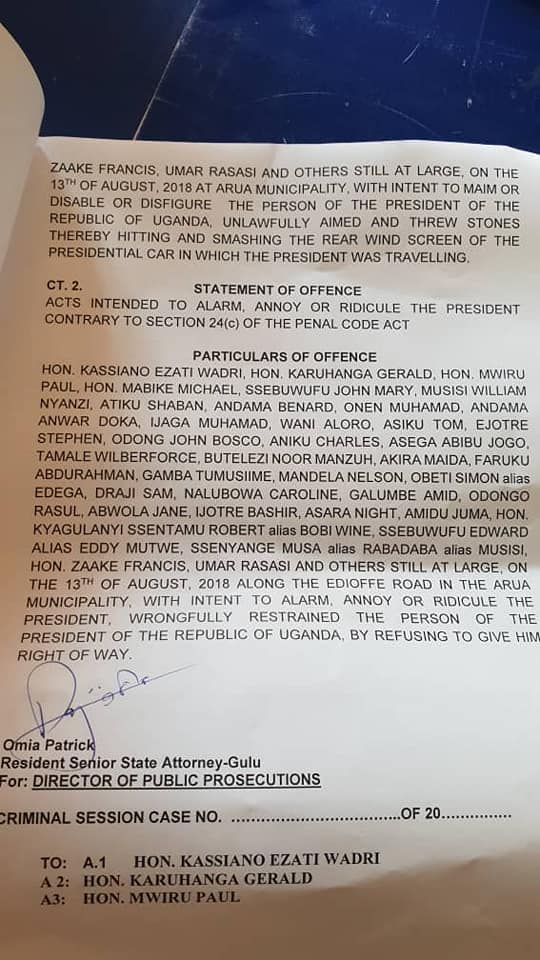

Bobi Wine, along with several opposition politicians and civilians, was arrested. One of Wine’s driver’s aides, Yasin Kawuma, was shot dead during the operation. The killing triggered nationwide outrage and drew international attention. As Bobi Wine was detained, police announced a series of dramatic claims: that guns had been found in his hotel room, that there was evidence linking opposition figures to the stoning of the presidential vehicle, and that alleged drugs had also been recovered during the operation.

The claims were serious and potentially devastating. Police paraded firearms and ammunition before the media, saying they had been recovered from Pacific Hotel. This was where Bobi Wine and other opposition figures were staying. Authorities accused him of unlawful possession of firearms. These charges were initially brought before a military court, despite Bobi Wine being a civilian legislator.

From the outset, the official narrative was fiercely disputed. Hotel management and witnesses denied that any weapons had been present before the security raid. They accused operatives of ransacking rooms and planting evidence. Bobi Wine and his lawyers flatly rejected the accusations. They called them politically motivated fabrications aimed at neutralising a rising opposition voice.

As weeks passed, the case began to unravel. The military court eventually dropped the firearms charges against Bobi Wine, and he was released. No clear public explanation was given as to why such grave allegations were abandoned. Equally unclear was the fate of the alleged guns themselves. Conflicting statements from security agencies raised doubts about where the weapons were being held, who had custody of them, and whether they were ever properly subjected to forensic examination.

The matter of the stoned presidential vehicle followed a similar trajectory. While authorities initially portrayed the incident as an attempted attack on the president, no conclusive prosecutions were secured. There was no clear link between Bobi Wine or other senior opposition figures to the act. The issue gradually faded from official discourse, despite its prominence at the time.

The alleged drugs, too, disappeared from public scrutiny. No detailed charge sheets, laboratory reports or court findings were ever widely presented to substantiate the claims. Like the gun allegations, the drug narrative quietly slipped out of the headlines.

Today, the 2018 Arua case stands as a powerful symbol of Uganda’s deeply polarised politics. For government supporters, the events justified a firm security response. For critics, the episode exemplified the use of state power, criminal charges and fear to suppress political dissent.

Years later, the central questions remain unanswered: What happened to the gun? What became of the case of the stoned M7 vehicle? And where did the alleged drugs go? The silence surrounding these issues continues to fuel mistrust in the justice system. This reinforces the belief among many Ugandans that some cases are never truly pursued to their legal conclusion — they simply vanish.