By Staff Reporter: Recent events have caused the Museveni Nakulabye quote to return to haunt him, stirring public discussion once more.

In December 1985, as Uganda stood at a crossroads after years of turmoil, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni delivered a speech that would later become one of the most frequently cited indictments of state violence in the country’s history. Speaking after signing the Nairobi Peace Agreement, Museveni declared:

“Violence in Uganda was not started by the people; but by those in power in 1964. The government started killing the people at Nakulabye.”

— Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, Daily Nation, December 18, 1985

Four decades later, that statement has returned to public discourse—not as a historical reflection, but as a mirror held up to Uganda’s present political reality. Critics now argue that the very abuses Museveni once condemned have re-emerged under the system he has led for nearly four decades.

A CYCLE OF POWER AND FORCE

The Nakulabye killings of the 1960s symbolized the use of state machinery to silence dissent and consolidate power. Museveni’s words in 1985 framed government violence as the original sin of Uganda’s instability. Today, opposition leaders, civil society groups, and international observers say similar patterns are visible: the deployment of security forces against civilians, the criminalization of dissent, and the erosion of constitutional freedoms.

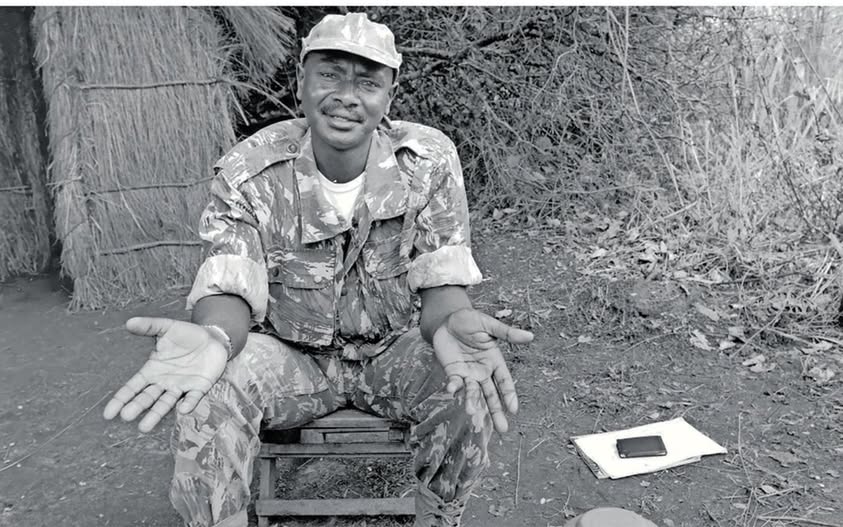

From election periods marked by violent crackdowns to routine arrests of journalists and activists, Uganda’s security landscape has expanded far beyond conventional policing. Military-style units now routinely manage civilian protests, political rallies, and even cultural gatherings.

Pull Quote:

“What we are witnessing is not law enforcement; it is political enforcement.”

SECURITY FORCES AND CIVILIAN ABUSE

Uganda’s security apparatus today includes the Uganda Police Force, the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), the Joint Anti-Terrorism Taskforce, Crime Intelligence units, and Local Defence Units. While officially tasked with maintaining order, these forces have repeatedly been accused of excessive force, illegal detention, and torture.

Opposition supporters recount being beaten during campaigns, arrested without charge, or held incommunicado in so-called “safe houses.” Human rights lawyers report a rise in enforced disappearances, particularly during politically sensitive periods.

“They came at night, no warrant, no explanation. Until today, my brother has never been produced in court.”

— Relative of a detained opposition supporter

Amnesty organizations have documented cases of civilians shot during protests, with security forces justifying lethal force as crowd control. These incidents echo the logic Museveni once criticized—where the state treats its citizens as enemies rather than stakeholders.

MUZZLING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Freedom of expression, once promised as a pillar of Uganda’s post-conflict future, has steadily narrowed. Independent radio stations are frequently suspended, journalists assaulted or arrested, and online activists charged under cybercrime and public order laws.

During election cycles, social media blackouts have become common, cutting off digital spaces where young Ugandans mobilize and express dissent. Public Order Management laws are routinely invoked to block opposition rallies while allowing pro-government events to proceed uninterrupted.

Pull Quote:

“The gun has replaced dialogue, and fear has replaced free speech.”

A veteran journalist in Kampala summed up the situation bluntly:

“You don’t need to be banned to be silenced. One arrest, one beating, and the message is clear.”

OPPOSITION UNDER SIEGE

Opposition leaders face repeated arrests, travel restrictions, and prolonged court cases that critics say are designed to exhaust and intimidate rather than deliver justice. Campaign convoys are blocked, supporters dispersed violently, and party offices raided.

The treatment of opposition figures has drawn comparisons to the pre-1986 era—ironically the very period Museveni cited as evidence of why armed resistance was once justified.

“When peaceful opposition is met with batons and bullets, the state forfeits its moral authority.”

— Human rights advocate

HISTORY’S IRONY

The most striking similarity between past and present lies in the justification of violence. In 1985, Museveni argued that state violence against civilians delegitimized those in power. Today, government spokespersons often frame crackdowns as necessary for stability, security, or economic progress—language eerily similar to past regimes.

Pull Quote:

“Violence by the state always wears the mask of ‘national interest.’”

Ugandans now ask whether the liberation narrative that once inspired hope has hardened into a system Museveni himself once condemned.

AN UNRESOLVED QUESTION

Museveni’s 1985 words remain a powerful benchmark against which the current regime is measured. If violence by those in power was wrong in Nakulabye, critics argue, it cannot be right in Kampala, Gulu, or Masaka today.

The unresolved question facing Uganda is not merely about leadership longevity, but accountability: can a state built on promises of freedom reconcile with accusations of repression?

As history watches, Museveni’s own words continue to echo—no longer as a warning about the past, but as an indictment of the present.