By Correspondent

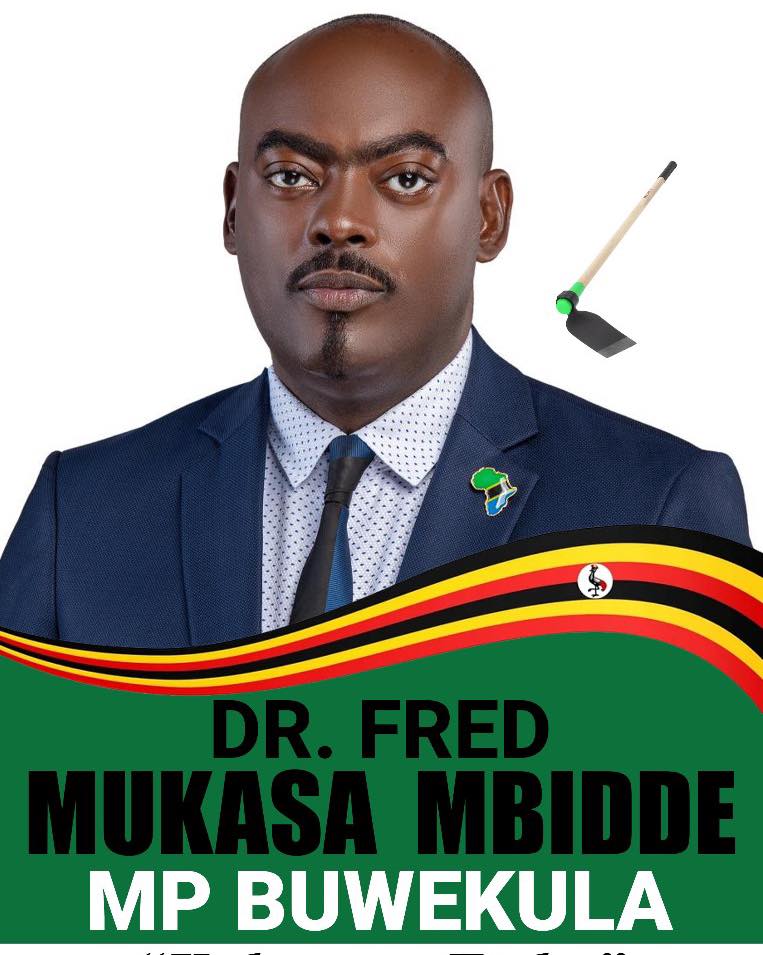

Kampala — Veteran lawyer and politician Fred Mukasa Mbidde has reignited the contentious debate over ancestry and identity among Uganda’s Banyarwanda (Kinyarwanda-speaking) communities, insisting that he is “a Munyarwa through my father” — a claim he says disqualifies the commonly used label “Maska.” The dramatic declaration comes amid mounting pressure over citizenship, documentation and representation ahead of the 2026 general elections.

At a rally in Kampala over the weekend, Mbidde, whose parents hail from the Ugandan south, startled many when he publicly affirmed:

“I’m a Munyarwa and I am going to be MP. My father is a Munyarwanda from Ruhengeri — not ‘Maska’!”

He stressed that ancestry should not be a barrier to political ambition or identity recognition, calling on authorities to treat Banyarwanda differently from recent immigrants or dual-citizenship claimants. According to Mbidde, years of marginalization and identity suspicion have undermined the rights of Ugandans of Rwandan heritage born and raised in Uganda.

Mbidde’s stance echoes his long-standing advocacy for citizenship reform. As legal advisor for the Banyarwanda community he has repeatedly challenged what he calls the “ethnicity-based citizenship system.” He argues for adoption of a stronger jus soli principle — granting citizenship to anyone born on Ugandan soil — to curb discrimination against communities whose documentation is often incomplete. Monitor+2Parliament Watch+2

The broader Banyarwanda conundrum

The Banyarwanda — including sub-groups such as the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa — have lived in what is now Uganda for generations, often predating the colonial border demarcation. Under the 1995 Constitution, they are listed among the indigenous communities present within Uganda’s borders by 1926. Monitor+1

Yet despite constitutional recognition, many Ugandan Banyarwanda still face structural hurdles: denial of national IDs, difficulties in obtaining passports, or being treated as foreigners. Parliament Watch+2Citizenship Rights Africa+2

Critics argue the system — which distinguishes citizenship by descent rather than purely by birthplace — leaves many legitimate Ugandans in limbo. For decades, community leaders and human-rights campaigners have denounced the practice as discriminatory. Monitor+1

Mbidde’s latest public claims come against this fraught backdrop.

Political reverberations — what Museveni and others say

President Museveni, in a high-profile 25 June 2025 meeting with leaders of the Banyarwanda community, reaffirmed the government’s commitment to protecting rights and identity of long-time residents — but drew a firm line on dual citizenship. Chimp Reports+2New Vision+2

“Those who have lived here for decades and are recognised by their local leaders are Ugandans,” Museveni said. “But what we cannot accept is dual citizenship without clarity. You must choose where you belong.” Margherita News+1

Museveni invoked his own background to illustrate the point: “Even I, as a Muhooro, know this. If I want to be Rwandan, I must go to Rwanda. I cannot claim both identities.” New Vision+1

Still, in the same address, he committed to protecting the welfare and legal rights of long-settled Banyarwanda. Margherita News+1

On the other hand, some constitutional-law experts and community advocates support Mbidde’s call for reform. A recent parliamentary petition rejected recommendations which they warned would “undermine the rights of Banyarwanda by birth.” Critics said those recommendations would relegate many to the status of “immigrants,” despite generations of uninterrupted residence in Uganda. Nilepost News+1

In a public post on social media, Mbidde lamented the government’s 2025 executive order on Banyarwanda citizenship, calling it a step backward:

“We reject the Executive Order on Banyarwanda Citizenship! It risks making over six million persons born in Uganda stateless.” X (formerly Twitter)

What’s at stake — beyond names and identity

Mbidde’s declaration and the reactions it has provoked underscore deeper fissures in Uganda’s social and political fabric. At stake are issues of belonging, representation and equal citizenship — particularly as Uganda heads into a heated 2026 election year.

For many Banyarwanda, the debate isn’t simply academic. It determines access to vital documents, political participation, land rights and social inclusion. A failure to resolve the matter could cement second-class status for large swathes of citizens, fuelling alienation, distrust, and instability.

Mbidde’s bold claim — that he is a Munyarwa and aspires to represent Ugandans in parliament — may test the government’s commitment to inclusion. But just as crucially, it may force Ugandans to confront how they define nationality in a country shaped by migration, colonially imposed borders, and diverse historic communities.

As Mbidde closed his rally, he declared:

“I stand here as proof that being Munyarwanda does not make me less Ugandan. If Uganda allows me to be MP, then many others like me will no longer live in uncertainty.”

Whether his ambition will translate into real political representation remains to be seen — but the spotlight on identity, ancestry, and citizenship rights is now shining brighter than ever.