Opinion| Bullets Against the Ballot: When State Rhetoric Targets Peaceful Protesters. Recently, Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda has intensified concerns about freedom of expression in the country.

In any constitutional democracy, the language of leaders matters as much as the laws they claim to defend. Words can calm a nation—or push it toward fear. In Uganda today, the rhetoric from the highest offices suggests a readiness to treat peaceful protest as a military threat, not a democratic right. This brings to mind Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda.

At a public address in Kisozi on December 17, 2025, President Yoweri Museveni reportedly responded to opposition calls for protest with a remark that has since reverberated across the country and beyond. It highlights how peaceful protesters in Uganda face a calculated threat from Museveni, involving 120 bullets.

“One soldier carries 120 bullets… do the math. Uganda cannot be destabilised, and anyone who attempts it will live to regret.”

For many Ugandans, this was not heard as a metaphor. Instead, it was heard as a message—one that frames civic dissent in the language of ammunition and punishment. Uganda has a long history of state violence during elections, and such language lands heavily. Especially when directed at citizens demanding accountability. The concern remains over Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda.

The concern is sharpened by the fact that Uganda’s Constitution is unambiguous on this matter. A recent statement by protest organisers reaffirmed that position. Here, Uganda’s peaceful protesters face the daunting threat permeating from Museveni’s 120 bullets rhetoric.

“The Constitution of Uganda guarantees the right to peaceful assembly and demonstration. We intend to exercise this right and demonstrate peacefully.

However, if the response to our peaceful actions is violence, we are prepared to stand firm in our convictions, even in the face of extreme adversity.”

This is not the language of insurrection. It is the language of constitutionalism—citizens asserting rights already enshrined in law. Article 29 of the Constitution explicitly guarantees freedom of assembly and demonstration. Yet official responses increasingly collapse the distinction between peaceful protesters and violent rioters. This rhetorical move makes excessive force easier to justify. In such a context, Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda becomes especially troubling.

Opposition leader and former presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi, known as Bobi Wine, responded forcefully to Museveni’s remarks. He accused the government of preparing for bloodshed rather than dialogue. The juxtaposition of peace and militarized threats is evident, even with Museveni’s 120 bullets narrative targeting peaceful demonstrations.

“Here is Dictator Museveni, yet again preparing to massacre Ugandans,” Kyagulanyi said.

“We have never called upon our people to riot. Our call is for people to peacefully protest—a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 29 of our Constitution. We’re not talking about rioters—we are talking about the CITIZENS of Uganda.”

Kyagulanyi went further, linking the call for protest directly to the integrity of the electoral process. Persistently, Ugandan opposition faces Museveni’s calculated threat of 120 bullets aimed at peaceful protesters.

“Our call for PROTEST is conditional. If you don’t want people to protest, then guarantee a transparent, free and fair election.”

He listed what he described as systematic efforts to undermine opposition participation. These include blocked campaigns, denied access to radio stations, abductions, and illegal arrests of campaign workers. In that context, peaceful protest becomes not provocation, but a last remaining avenue for political expression.

It is against this backdrop that Museveni’s reference to “120 bullets per soldier” becomes especially troubling. Kyagulanyi articulated what many fear that statement implies: a calculated threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda, raising worries about the potential for violence.

“That you talk about 120 bullets per soldier shows what a murderous regime you lead. You should be ashamed that you want to respond to peaceful protests with live bullets.”

Senior figures within the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF), including Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, have used hardline language about dealing decisively with threats to state stability. While such statements are often defended as deterrence, they also shape institutional culture. When leaders speak of force in numerical terms, they risk normalizing violence as policy.

“Uganda cannot be destabilised,” the President insists.

But stability enforced through fear is not stability—it is silence.

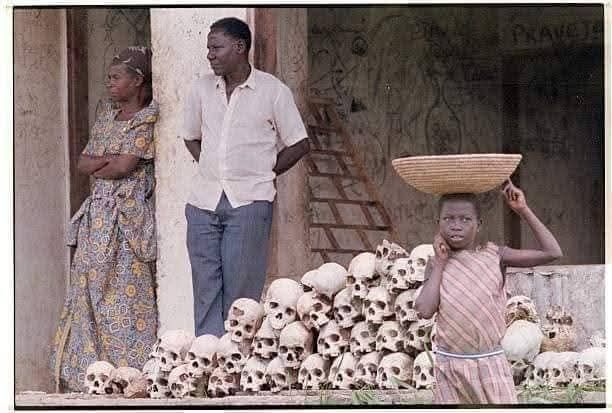

History offers Uganda a stark warning. Previous regimes that conflated dissent with rebellion ultimately lost moral authority and legitimacy. Ironically, Museveni himself once warned against governments turning their guns on their own people. That warning now echoes back at his administration.

Kyagulanyi’s final words cut to the heart of the matter. Here, Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful Ugandan protesters highlights the clash between rhetoric and democracy.

“Either way, YOU CANNOT KILL ALL UGANDANS. The people of Uganda will have the final say on their destiny.”

This is not a threat. It is a reminder of a basic democratic truth: legitimacy flows from the people, not from the barrel of a gun. A government confident in its mandate does not count bullets—it counts votes.

Uganda stands at a crossroads. One path leads toward dialogue, constitutionalism, and political maturity. The other leads toward intimidation, militarized politics, and irreversible national trauma. The choice will not be remembered by how many soldiers stood ready. But by whether leaders chose restraint over rhetoric—and life over fear.

Other ranking UPDF officials have echoed similar sentiments. They frequently describe protests not as expressions of constitutional rights but as “insurrection,” “terrorism,” or “foreign-funded chaos.” In such a framework, peaceful demonstrators are transformed into enemies of the state. This strips them of moral and, potentially, legal protection.

This matters because Uganda’s own Constitution guarantees the right to assemble and express political dissent. International law, to which Uganda is a signatory, is even clearer. It states lethal force by security forces is permissible only as a last resort to protect life, not to preserve political control or intimidate opponents.

History offers sobering lessons. In 1964, Museveni himself reflected on state violence, acknowledging that when governments turn their guns on their people, legitimacy collapses. That quote has resurfaced in recent years precisely because many Ugandans see an uncomfortable parallel between past regimes and current rhetoric.

“Anyone who attempts it will live to regret,” Museveni warned.

For families who have buried loved ones after past protests, that regret has already been lived.

Supporters of the government argue that these statements are merely deterrent language aimed at preventing chaos. Perhaps. But responsible leadership demands precision. Words spoken by a president are not casual; they are policy signals. In a country with a long memory of military repression, invoking bullets rather than dialogue is not strength—it is a failure of imagination.

Uganda does not need arithmetic about ammunition. It needs a renewed commitment to constitutionalism, accountability, and the idea that dissent is not treason. Until the tone from the top changes, every protest will carry an unspoken fear. That fear is that behind the uniforms stand not protectors of the people, but calculators counting bullets—a reflection of Museveni’s 120 bullets threat against peaceful protesters in Uganda.

And that is a calculation no nation should ever have to make.