By an Investigative Journalist

In the heated run-up to Uganda’s next election cycle, the country’s political landscape has once again revealed a troubling double standard. This raises serious questions about state neutrality, freedom of expression, and selective outrage. At the center of this controversy is something almost absurd: toy guns made from yam plant stems.

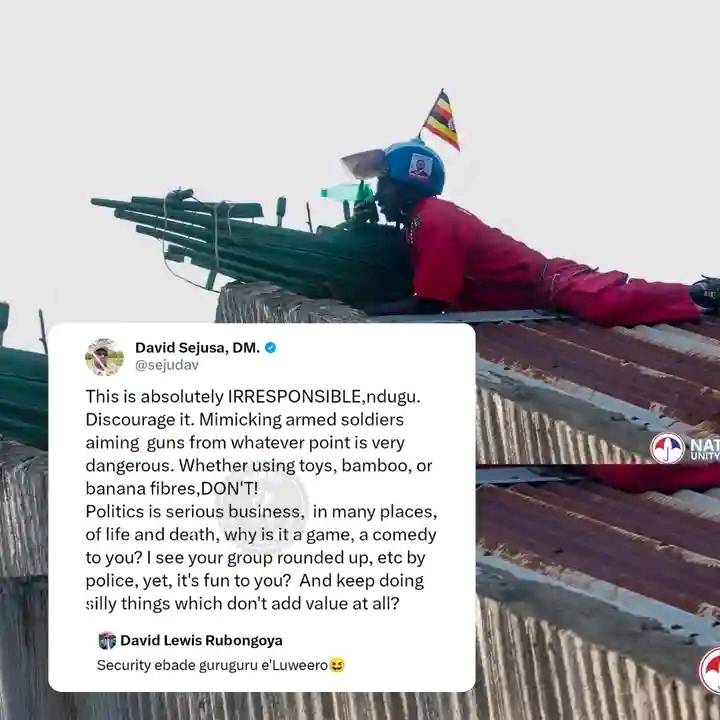

Recently, Acting UPDF spokesperson Chris Magezi publicly accused supporters of the National Unity Platform (NUP) in Luwero of “mocking the army.” This accusation followed images that circulated of youths holding makeshift toy guns fashioned from plant stems. Magezi warned that such actions could “cause mayhem” in an already tense election period.

“These so-called toy guns are not a joke in an election season,” Magezi reportedly cautioned, framing the imagery as a potential threat to public order.

The warning was swift, stern, and widely amplified by pro-government media outlets. The message was clear: symbolism, even when crude and clearly non-functional, would not be tolerated. At least when it came from NUP supporters.

But then something curious happened.

An image of a ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) supporter posing proudly with a toy gun of his own went viral on social media. The object was no less symbolic, no more real, and no less capable of “mocking the army” than the yam-stem replicas previously condemned. Yet this time, there was no alarm.

No press statement.

No tweet.

No warning about “election mayhem.”

“Silence can be louder than condemnation,” observed one political analyst, noting the abrupt disappearance of the army spokesperson’s voice.

Since that image surfaced, Magezi has gone quiet—what critics mockingly describe as “Airplane Mode.” The contrast has not gone unnoticed by the public. Particularly, opposition supporters see the silence as confirmation of long-held suspicions: that the rules are applied differently depending on political allegiance.

This is not merely a debate about toy guns. It is about power, perception, and selective enforcement.

Uganda’s security agencies insist they are non-partisan, professional, and guided strictly by law. Yet incidents like this continue to erode public trust. When symbolic acts are criminalized on one side and ignored on the other, the message to citizens is unmistakable: justice is political.

“Maybe the toy gun only becomes dangerous depending on the colour of the T-shirt behind it,” one activist remarked, summing up the public mood with biting sarcasm.

The deeper issue lies in how state institutions respond to dissent. NUP, as the main opposition force, has long accused security agencies of intimidation, harassment, and unequal treatment. From blocked rallies to arrests over symbolic gestures, the party argues that even satire is treated as subversion.

Meanwhile, similar conduct by ruling party supporters is often brushed off as harmless enthusiasm.

In an election season already marred by fear, this selective outrage risks inflaming tensions rather than calming them. If toy guns made from plant stems can be framed as a security threat, where does that leave freedom of expression, political symbolism, or even humor?

“When institutions speak only when it suits power, they stop being institutions and become instruments,” warns a governance researcher.

As Uganda moves closer to another high-stakes election, the silence surrounding the NRM toy gun episode speaks volumes. It suggests that the issue was never really about public safety—but about who is allowed to express themselves without consequence.

And in that silence, many Ugandans hear a familiar truth. In today’s politics, even a toy can become a weapon—if it’s held by the wrong hands.